In this class, we will read, discuss, and write short works of prose designed to evoke surprise by thwarting your automatic mind and your reader’s expectations. I hope you’ll find these sentence-level techniques valuable and adaptable.

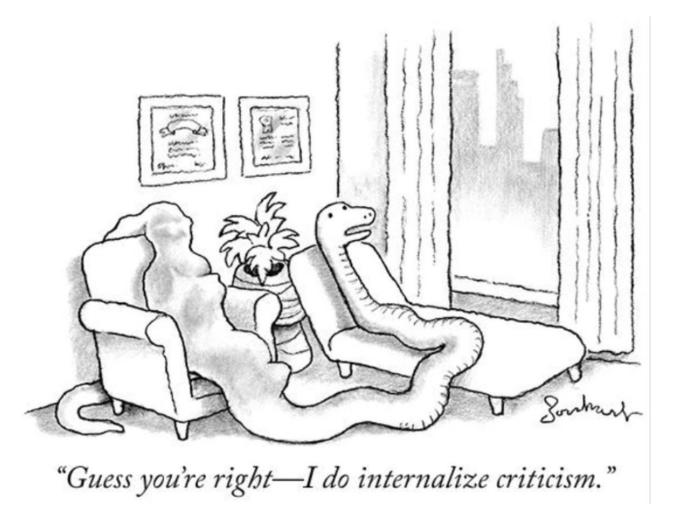

Perhaps you find the idea of surprises corny. Perhaps the word “thwarting” resonates as stingy and manipulative, even downright deceptive, but technically that’s what surprise is: thwarted certainty. You’re certain a thing will happen, but it doesn’t, or certain a thing that can’t possibly happen does. Imagine you’re in your living room on a rainy afternoon watching Netflix when a possum casually waddles in. Wait…is that really a possum? You’ve never seen a possum up close, but you’re 99% sure that that greasy ghost-faced Muppet with beady black eyes and a nasty pink tail is a possum. “What the…?” you gasp. It humpty-dumps across the rug then fwoop—disappears under the couch. The impossible has happened. You pull on your tallest leather boots and heaviest gloves, prop open the front door, and grab the broom. Your plan is to skooch the couch away from the wall and shoo the possum out. Nothing. You skooch the couch further and further from the wall, until—with one eye on the floor and the other on the door—you flip the whole thing over to find…a pair of nail clippers, dust bunnies, but no possum. The impossible has happened again. You never expected to see a possum, but then you did, and now its absence will haunt you for the rest of your life.

The mechanism of surprise will help you hold the reader’s attention. In her book, Elements of Surprise: Our Mental Limits and the Satisfactions of Plot, Neuroscientist Vera Tobin explains that surprised readers are more engaged with the page, because the surprised brain releases dopamine, which heightens our pleasure and sense of connection to the text and our fellow humans. Yahtzee! Dopamine engages the reward center of our brains, which scientists believe is an adaptive response.

Moreover, studies have shown that surprise increases the intensity of all feelings—not just happy ones—a whopping 400%.

“Until recently, scientists assumed that the neural reward pathways, which act as high-speed Internet connections to the pleasure centers of the brain, responded to what people like,” Read Montague of Baylor College of Medicine explains. “However, when we tested this idea in brain scanning experiments, we found that reward pathways responded much more strongly to the unexpectedness of stimuli instead of their pleasurable effects…This means that the brain finds unexpected pleasures more rewarding than expected ones, and it may have little to do with what people say they like.” —Scientific American

Surprised readers are also more likely to find your story unforgettable—literally—because surprise enables us to retain what we’ve read longer; surprise is, in fact, one of the greatest predictors of information retention.

Creating surprise requires empathy and an understanding of what other people know. The flip side of this coin is subjectivity—the voice emanating from our unique personal histories, bodies, families, and perspectives—the voice that undoubtedly drew you to writing in the first place. We start writing for ourselves, for the way it makes us feel, for the permission and power it gives us to reexamine our stories. It is this unique, subjective voice that will draw readers in. So if you’re thinking, “Forget faceless readers. I want to show The World what it's like to live in my skin,” you don’t have to choose. Engaging writing incorporates both cardinal points on the compass—subjectivity and empathy. Any jazz musician will tell you, when the band swings from solo to synchronicity and back again, that’s when the audience goes apesh*t.

The shift between the objective and subjective, the group and the individual, can occur subconsciously, in mid-sentence, much like in the murmurations of starlings. Note how the solo birds zip willy-nilly on the edges of the swarm until suddenly—boom—they sync with the undulating mass, disengage, sync, disengage, ad infinitum.